“Africa” latest body of work currently on exhibit at the Peter Fetterman Gallery in Santa Monica, California also includes photographs of Sebastio Salgado’s current project “Genesis”. “Genesis” should be completed in 2012 and plans are being made to display this ecological photo essay in Central Park, New York City.

SEBASTIÃO SALGADO sounds as if he’s slightly allergic to Los Angeles. It’s not just that this celebrated Brazilian photojournalist has been sniffling since he arrived in the city, explaining: “I was born in a tropical ecosystem. I’m not used to these plants.” It’s also that he peppers his description of the city with words like strange and crazy, noting that he was mesmerized by the sight of the endless stream of automobile traffic as his plane made its descent.

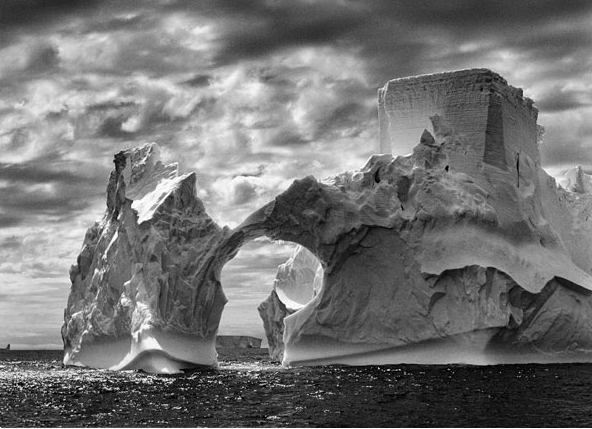

The urban sprawl of Los Angeles is, in any case, a far cry from the remote, sparsely populated jungle and desert locations where he has been traveling for his epic, ecological work in progress “Genesis.” Famous for putting a human face on economic and political oppression in developing countries, Mr. Salgado is photographing the most pristine vestiges of nature he can find: pockets of the planet unspoiled by modern development. He has visited the seminomadic Zo’e tribe in the heart of the Brazilian rain forest and weathered desolate stretches of the Sahara. Next up: two months in the Brooks mountain range of Alaska on the trail of caribous and Dall sheep.

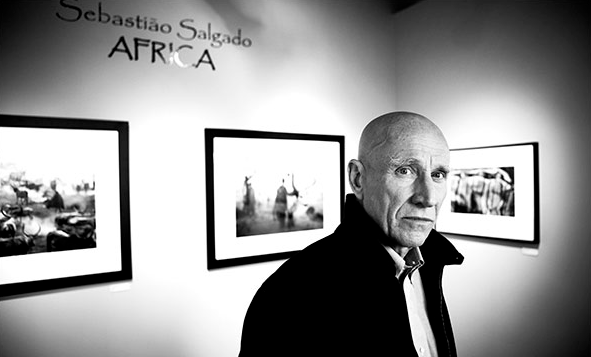

But this brand of environmentalism is costly enough to send him back to major cities for support. That’s what brought him here for a three-day whirlwind of talks, meetings and parties. One night he gave a slide show featuring new work from “Genesis” to a sold-out crowd at the Hammer Museum. The next evening he was a guest of honor at a fund-raiser at the Peter Fetterman gallery in Santa Monica, where some of his new work appears in his show “Africa,” through Sept. 30. After that it was off to San Francisco for a benefit dinner given by Marsha Williams before returning to Paris, which he considers home along with Vitória, Brazil.

It might sound like a punishing schedule, but the 65-year-old photographer says he doesn’t mind and doesn’t lose focus on work even when flocked by art collectors and celebrity backers. Sitting down at the Peter Fetterman gallery, with his image of zebras in Namibia hanging overhead, Mr. Salgado compared his time away from nature to the potentially disruptive moment when he has to change the film in his camera, when he likes to close his eyes and sing so as not to lose concentration.

“I came here for special things, but my head is there, my body is there,” he said with an intent expression and a gentle Portuguese accent. “I might be sleeping in a hotel room in Los Angeles, but in my mind I am always editing pictures.”

For “Genesis,” an eight-year project now more than half completed, he is piecing together a visual story about the effects of modern development on the environment. Yet rather than document the effects of, say, pollution or global warming directly, he is photographing natural subjects that he believes have somehow “escaped or recovered from” such changes: landscapes, seascapes, animals and indigenous tribes that represent an earlier, purer — “pristine” is a favorite word — state of nature.

In this way “Genesis” is a grand, romantic back-to-nature project, combining elements of both the literary pastoral and the sublime. Mr. Salgado also describes it as a return to childhood, as he was raised on a farm in the Rio Doce Valley of southeastern Brazil — then about 60 percent rain forest — that suffered from terrible erosion and deforestation. Years later, in 1998, he and his wife, Lélia, founded the Instituto Terra on 1,500 acres of this land to undertake an ambitious reforestation project. His wife, who also designs his books and exhibitions, is the institute’s president; he is vice president and the institute’s most famous spokesman. Or, as Ian Parker wrote in The New Yorker, Mr. Salgado is more than a photojournalist, “much the way Bono is something more than a pop star.”

In short, while the Instituto Terra is the locally rooted arm of his environmental activism, “Genesis” is its globally minded, photo-driven counterpart. Since undertaking the series in 2004, he has visited some 20 different sites across 5 continents.

He began with a shoot in the Galápagos Islands that paid homage to Darwin’s studies there. (Mr. Salgado says his title, “Genesis,” is not meant to be religious.) “Darwin spent 37 to 40 days there,” he said. “I got to spend about three months there, which was fabulous.” He was thrilled to see for himself evidence of natural selection in species like the cormorant, a bird that lost its ability to fly after a history of foraging for food underwater, not by air.

Last fall he spent two months in Ethiopia, hiking some 500 miles (with 18 pack donkeys and their owners) from Lalibela into Simien National Park to shoot the mountains, indigenous tribes and rare species like a very hairy baboon known as the Gelada. “I was traveling in this area in the same way people did 3,000 to 5,000 years ago,” he said.

Well, almost the same way. He did carry a satellite phone, which made him the point person for receiving news of the United States election in November. “When we found out that Obama won, everyone driving these donkeys, everyone was jumping up and down,” he said. He called Mr. Obama’s election “a victory for the planet.”

He is cautiously optimistic about his own environmental work. “I’m 100 percent sure that alone my photographs would not do anything. But as part of a larger movement, I hope to make a difference,” he said. “It isn’t true that the planet is lost. We must work hard to preserve it.”